Measuring the Blue Marble

Landmark Earth Measurements Revisited

Earth is the most extensively studied corner of the universe.

Yet, even the most trivial of its properties such as rotation and weight were made known to us only a few hundred years ago.

What is fascinating is that none of the measurements done to discren these properties ever required us to leave the surface of the Earth.

Not for once.

All that was needed was the knowledge of some basic truths and a bit of human ingenuity.

So that’s what we will revisit today.

Eratosthenes’ Measurement

Spherical Shape of Earth

Earth was initially thought of as flat.

Evidently, any patch of land close enough to our point of observation roughly lies in a plane. Yet, even in 500 BCE, there were some who believed this not to be the case.

Pythagoras believed that sphere was the most perfect shape.

So, he was the first to propose a spherical Earth. But, this was done mainly on aesthetic grounds rather than on any physical evidence.

Aristotle seems to be the first to propose a spherical Earth based on actual physical evidence.

His arguments for this belief are as follows -

- Ships disappear hull first when they sail over the horizon

- Earth casts a round shadow on the moon during a lunar eclipse

- Different constellations being visible at different latitudes

We will consider the spherical Earth hypothesis as our starting point.

Now, if Earth is truly a sphere, then it must have a circumference like any other sphere.

Earth casts a round shadow on the moon during a lunar eclipse

(Source : https://www.esa.int/ESA_Multimedia/Images/2007/03/The_moon_leaving_the_Earth_s_shadow_again)

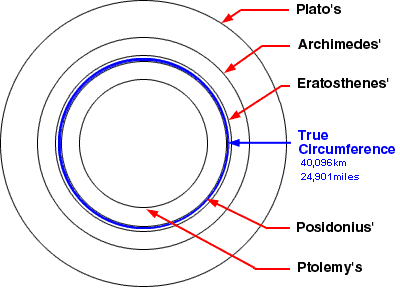

Several attempts were made by Greeks to determine the same.

And one in particular stood out for its remarkable accuracy.

Calculating the Circumference of Earth

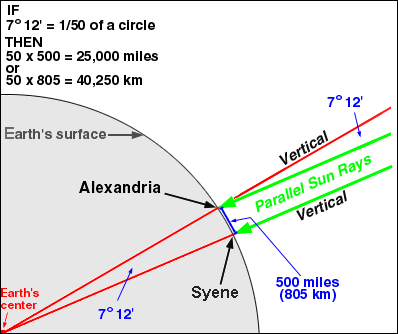

In 3 BCE, Eratosthenes of Cyrene determined the earth’s circumference.

The Greek astronomer did so by comparing the Sun’s relative position at two different locations on the earth’s surface.

The 2 locations were Syene (today : Aswan, Egypt) and Alexandria.

In Syene, he noticed that the sun’s rays shone directly down a well, casting no shadow at all. This meant that the sun was directly overhead at Syene.

On the same date in Alexandria, a rod perpendicular to the ground cast a shadow that was 7°12’ from perpendicular.

7°12’ is 1/50th of a circle (360⁰).

So, only if Eratosthenes knew the distance between the 2 cities, he would be able to multiply the distance by 50 to obtain Earth’s circumference.

Eratosthenes determined the distance between the cities of Alexandria and Syene and multiplied it by 50 to get Earth’s circumference.

(Source : http://www.geo.hunter.cuny.edu/~jochen/gtech201/lectures/lec6concepts/datums/determining%20the%20earths%20size.htm)

Many scholars believe Eratosthenes measured the distance by measuring a single pace and then counting the number of paces from Syene to Alexandria.

The distance figure he used was 805 km.

Proceeding with the calculation, this distance was multiplied by 50 to get 40,250 kilometers.

Comparing his estimate of 40,250 km with today’s accepted value (40,096 km), the error is less than 1 percent.

This makes Eratosthenes’ measurement a remarkable approximation of the Earth’s circumference.

Error in Measurement

Now that we have looked at the estimate, we must also understand the sources of error.

Firstly, Eratosthenes had made the assumption that the sun was so far away that its rays were essentially parallel.

And for sun rays to fall overhead on Syene on the Summer Solstice, it must have been on the Tropic of Cancer.

In reality, it is 37 km north of the same, hence, contributing to the error.

Moreover, Alexandria NOT due north of Syene. Even the distance between them is NOT 805 kilometers.

The actual distance corresponds to an angular measurement of 7°30’ instead of the 7⁰12’ used in the calculation.

Yet, the accuracy of his measurement far exceeded the attempts by any of his contemporaries.

Comparison of the estimates of Earth’s circumference by various Greek mathematicians

(Source : http://www.geo.hunter.cuny.edu/~jochen/gtech201/lectures/lec6concepts/datums/determining%20the%20earths%20size.htm)

Foucault Pendulum

Helio-centric model requires Rotation of Earth

The stars appear to move in circles about the line through the poles of the Earth.

An ancient explanation of this phenomenon is that stars are attached to a sphere which rotates about the Earth.

In 3 BCE, Aristarchus of Samos proposed that the Earth turns on its own axis and also travels around the Sun. This, he believed, explained the apparent motion of the stars and planets.

This view was rejected by Hipparchus (2 BCE) and Ptolemy (2 CE) for the following two reasons -

- One cannot feel the rotation of the Earth while being present on its surface

- Without powerful telescopes, one cannot see annual changes in the relative position of the stars

So, the geo-centric (Earth-centred) view dominated European science until the seventeenth century.

But, eventually, this geo-centric gave way to Copernicus’ helio-centric (Sun-centered) model of the Solar system.

The first point regarding the inability to feel the rotation is a consequence of the low rate of rotation of Earth required in this helio-centric model. To be precise, the rate would be 0.0007 revolutions per minute.

We know that we cannot practically feel this rotation.

But, could there be a way to at least prove it exists ?

Proving the Rotation of Earth

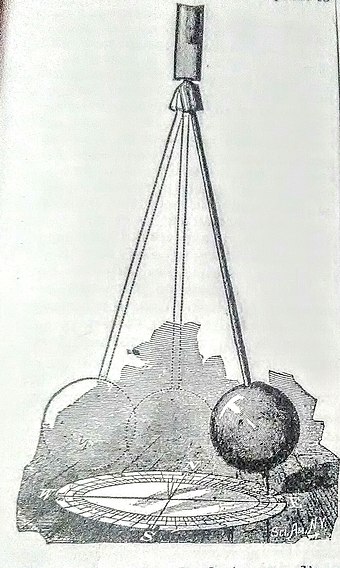

In 1851, Jean Foucault suspended a 67 metre, 28 kilogram pendulum from the dome of the Pantheon in Paris.

The plane of its motion, with respect to the Earth, rotated slowly clockwise.

This motion is most easily explained if the Earth itself turns or rotates.

(anticlockwise as viewed from the Northern hemisphere, clockwise from the South).

1895 print of the original Foucault pendulum

(Source : https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foucault_pendulum)

Suppose someone put a pendulum above the South Pole and sets it swinging in a simple arc.

To someone directly above the Pole and not turning with the earth, the pendulum would seem to trace repeatedly an arc in the same plane while the earth rotated slowly clockwise below it.

To someone on the earth, however, the earth seems to be stationary, and the plane of the pendulum’s motion would seem to move slowly anticlockwise, viewed from above.

We say that the pendulum’s motion precesses.

Subtleties to the Pendulum

The precession of the pendulum may have proved Earth’s rotation.

But, its rate of precession is NOT equal to the rate of rotation of Earth. This is because the period of precession of the pendulum is different at every latitude.

Infact, on the equator, the pendulum would not precess at all. So, its precession period would be infinite.

Only at the North and South Pole, the precession period exactly equal to the length of a day - 23.93 hours.

At intermediate latitudes the period has intermediate values.

To be precise, for a latitude θ (0≤θ≤90), the precession period is 23.93 / sin(θ) hours.

Cavendish Experiment

Cavendish (Torsion) Balance

Henry Cavendish was the first to calculate the gravitational constant (G).

He did this by measuring the force of gravity between two masses in a laboratory framework.

The original experiment was proposed by John Michell (1724-1793), who first constructed a torsion balance apparatus.

In 1793, the apparatus was passed to Henry Cavendish who carried out a series of experiments with it.

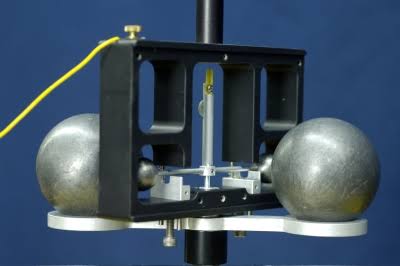

Cavendish Balance

(Source : https://sciencedemonstrations.fas.harvard.edu/presentations/cavendish-experiment)

The original apparatus included a 1.8 m wooden rod with metal spheres attached to each end, suspended from a wire. Five 350 lb (195 kg) lead balls were placed nearby.

The gravitational force exerted on the end weights was enough to cause the wire to twist.

From the twisting torque on the wire and the known masses of the spheres, Cavendish was able to calculate the value of the gravitational constant.

Calculation for G

Note : The following method of calculation differs from that used by Cavendish (reason explained in the subsequent section).

The section describes how modern physicists calculate the results from his experiment.

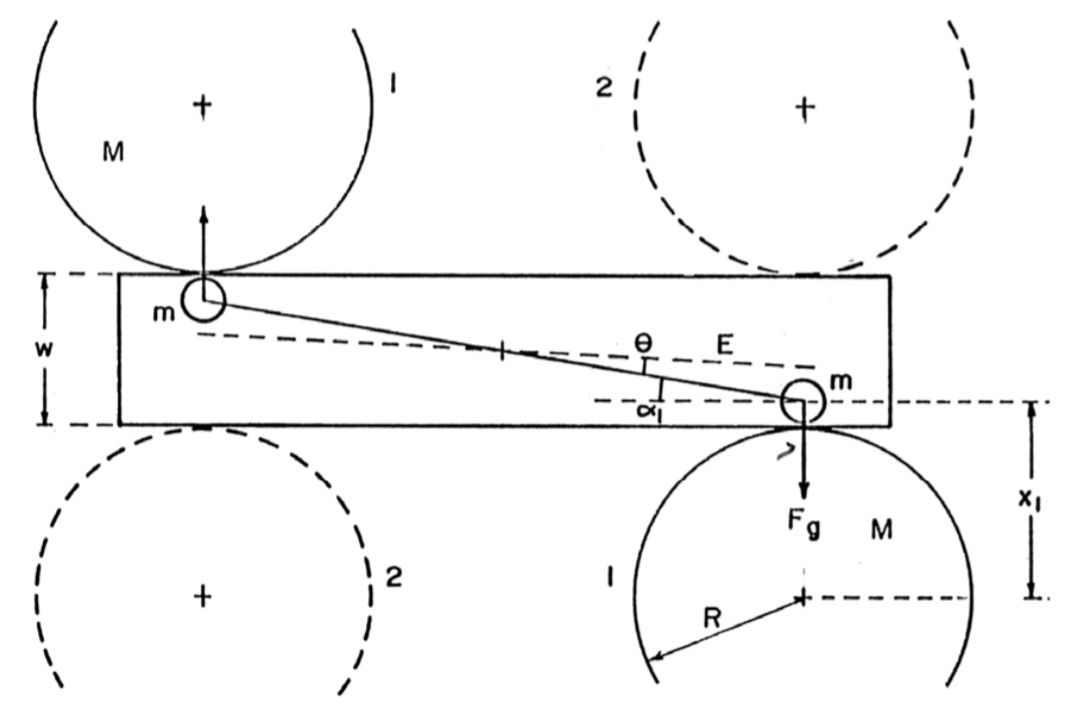

Schematic Diagram of Cavendish Balance

In the figure, the position labeled E is the equilibrium position of the balance in the absence of the masses M.

When the masses M are placed in position 1, they exert gravitational force on the small masses m.

This force F_g is equal to GMm/x².

\[F_{g} = \frac{GMm}{x^{2}}\]G is the Universal Gravitational constant and x (labelled x_1 in the figure) is the distance between the centers of masses m and M.

The force F_g acts on both the m, forming a couple.

The resultant (sum) of a couple of forces is ZERO. But, it produces a net moment (torque).

Thus, the torque τ_g on the inner frame is (GMm/x²)(2d cos(α)).

\[\tau_{g} = \frac{GMm}{x^2}2dcos(\alpha)\]2d is the distance between the masses m and α is the angle made by inner frame with its initial orientation.

At equilibrium, this torque is balanced by a torque from the wire supporting the inner frame which acts as a torsion spring. This torque is given by kθ, where k is the torsion constant and θ is the angle of twist of the wire.

So, kθ = (GMm/x²)(2d cos(α))

\[k\theta = \frac{GMm}{x^2}2dcos(\alpha)\]This k can be determined by measuring the period T of oscillation as the frame approaches equilibrium and its moment of inertia I.

They are related as follows : k = 4π²I/T².

\[k = \frac{4\pi^2I}{T^2}\]In an ideal massless frame, only the masses m would contribute to the moment of inertia. So I would be equal to 2md².

\[I = 2md^2\]Using the given equations, we can eliminate m from our calculations.

Moreover, α=θ, since internal angles are equal.

\[\frac{4\pi^2d^2}{T^2}\theta = \frac{GM}{x^2}dcos(\theta)\]One last step.

The distance x between centre of masses of M and m can be calculated using geometry. Obviously, it is R + w/2 - dsin(θ).

\[x = R + \frac{w}{2}-dsin(\theta)\]Here, w is the width of the case.

Using appropriate values and approximations the value of ‘G’ can be calculated as 6.74×10^−11 m^3 kg^–1 s^−2.

\[G = 6.74×10^{−11} m^3 kg^{–1} s^{−2}\]Density of Earth

Cavendish’s original result was expressed in terms of Earth’s density.

That is the reason for differing calculations ads mentioned in the previous section.

This is because the formulation of Newtonian gravity in terms of a gravitational constant did not become standard until long after Cavendish’s time. Infact, one of the first references to G is in 1873, 75 years after Cavendish’s work.

So, he referred to his experiment as ‘weighing the world’.

Using the torsion balance, Cavendish had measured the gravitational force between the masses M and m. Moreover, the gravitational force of the Earth on ball of mass m could be measured directly by weighing it.

The ratio of these two forces allowed the relative density of the Earth to be calculated. This gave Cavendish his result.

Cavendish found that the Earth’s density was 5.448±0.033 times that of water. The current accepted value is 5.514 g/cm3.

The experiment is now used to calculate G instead of the density of Earth.

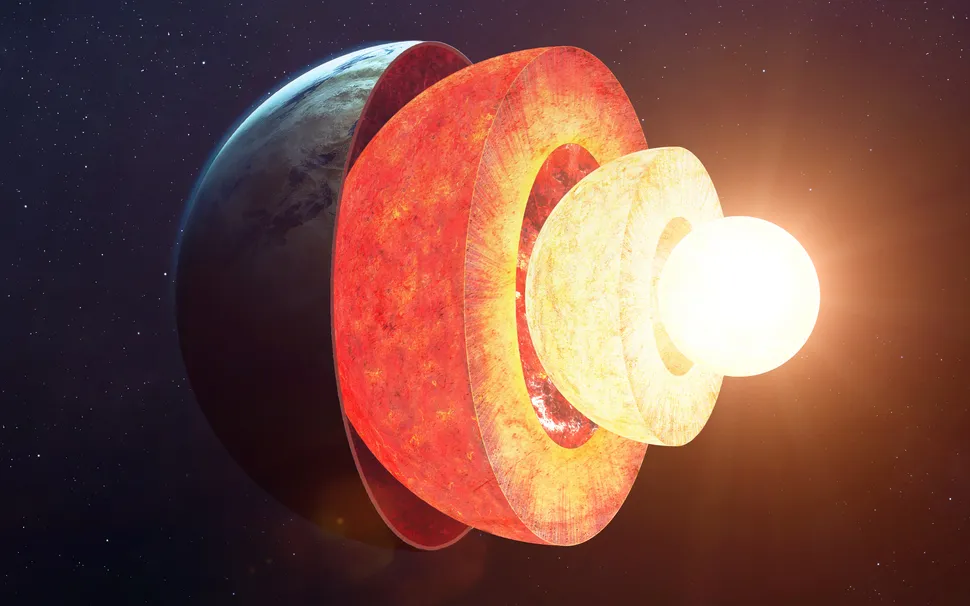

Evidence for Iron Core

Interestingly, Cavendish’s result also provided additional evidence for a planetary core made of metal.

The idea of a metal core was first proposed by Charles Hutton based on his analysis of the 1774 Schiehallion experiment.

Cavendish’s result is close to 80% of the density of liquid iron.

Thus, suggesting the existence of a dense iron core.

Cavendish experiment provided additional evidence for Earth’s Iron Core

(Source : https://www.space.com/earth-innermost-inner-core-metallic-ball)

References

- http://www.geo.hunter.cuny.edu/~jochen/gtech201/lectures/lec6concepts/datums/determining%20the%20earths%20size.htm

- https://www.aps.org/publications/apsnews/200606/history.cfm

- https://www.animations.physics.unsw.edu.au/jw/foucault_pendulum.html

- https://www.physics.utoronto.ca (Cavendish Experiment)

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cavendish_experiment